Me acaba de llegar el enlace de Internet del último número del Nieman Report de la Universidad de Harvard sobre «Coraje en el periodismo».

Incluye un artículo mío, corregido -claro- por mi chica, sobre la conquista de la libertad en España palabra a palabra.

Son reflexiones que cualquier asiduo a este blog conoce de sobra, pero las incluyo aquí, aunque están en inglés, porque no pierdo la esperanza de traducirlas al castellano y conservarlas en este archivo, en la sección de «recuerdos de periodistas».

En realidad fueron mis colegas Nieman de Harvard (y mi familia) quienes me convencieron de que escribiera, por primera vez en 30 años, sobre mi secuestro al final de la dictadura de Franco. Lo hice primero en este blog y luego lo resumí para ellos en este artículo.

Nieman Reports

Summer 2006 Issue

Summer 2006 Table of Contents > Reflections on Courage: International >

Climbing to Freedom Word By Word

Reflections on Courage

International

Climbing to Freedom Word By Word

‘… our ethical and political convictions gave us strength to resist and keep advancing.’

By Jose A. Martinez-Soler

I will never know if I am a courageous or cowardly journalist, especially while being tortured or facing a mock firing squad execution of a paramilitary commando. In those horrific circumstances, which happened to me on March 2, 1976, my body was battered black and blue, my face burned and bloody, and a gun was pointed at my forehead two hand-lengths away. A kidnapper was slowly counting; he would shoot me on three if I did not reveal the identity of my sources. Those guarding me from behind stepped aside, as their footsteps rustled the leaves.

Coverage of Martinez-Soler’s

kidnapping and beating in the

(London) Sunday Times

I do not know if I would have had the courage to keep secret the names of my sources, but I did not betray my sources because I never knew their real names. My confidential military sources knew what they were doing and wisely protected their identity with pseudonyms, while the investigative clues they gave me were easily confirmed in the Official Bulletin of the Army and involved the systematic transfer, i.e. the purging, of democratically minded high-ranking generals to isolated rural areas. Would I have betrayed them had I known their identity? Perhaps, but I will never know.

Ever since that traumatic day, I’ve never considered myself a courageous journalist. I understand those who «tell all» under torture, and I understand fear.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

General Francisco Franco led a military coup against the democratically elected government of Spain’s Second Republic in 1936. Franco ruled Spain until his death in November 1975.

On that day, four or five hooded men armed with machine guns and pistols blocked my car as I was leaving my home in the outskirts of Madrid. They burned my face with a spray, handcuffed me, and drove me to an isolated spot near the top of Sierra Guadarrama, northwest of Madrid. There they interrogated me for nine or 10 hours using the traditional methods of torture to obtain the desired information. I was «obliged» to sign an official declaration that was to be used against two top ranking generals of the Civil Guard whom they considered anti-Francoists.

Just before nightfall, the kidnappers abandoned me in the mountains but threatened to kill me and my wife, Ana Westley, also a journalist, if I ever denounced what had happened. I was terrified. After leaving the hospital, where Ana and I felt unsafe, we decided that I could at least try to annul my «official» declaration. I went to a night court and said that I had been beaten and was forced to sign something official, «three carbon copies,» but that I suffered from traumatic amnesia and could not remember details. After I did that, we received death threats over the telephone while journalists demonstrated (illegally) in the streets.

RELATED WEB LINK

«My Kidnapping: A day like today, 30 years ago …» (PDF)

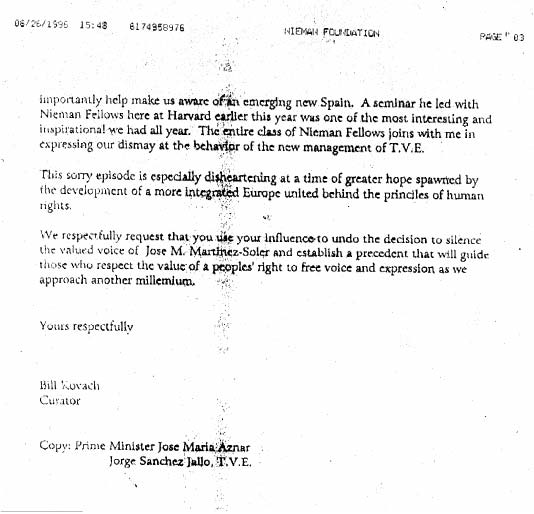

For convalescence, we went into hiding for several weeks. Upon our return home there were more death threats. We were given police protection, and I applied to the Nieman Foundation. Ever since the kidnapping, I have been afraid to confirm publicly, in writing, the details — just in case. In an exercise of catharsis, as I prepared this article, for the first time I have written a full account of the experience, which is now on my personal blog, along with some pictures taken of me in the hospital.

Journalism in a Dictatorship

In writing now about this experience, I want to reflect about what happens to the practice of journalism when one’s words are subjected to official censorship or when freedom of expression is threatened. One thing I have learned is when readers live in a dictatorship, they know that the supreme source of information is the dictator. Therefore, they distrust the official press and believe very little of what journalists, who are bound by censorship and hobbled by judicial threats, publish. Yet they’re able to decipher facts and opinions written between the lines, so as journalists we work hard to establish a privileged thread of communication through complicit winks, subtleties, humor and layered meanings that are largely invisible to censors.

Franco’s dictatorship controlled the large tectonic plates of Spanish society, but journalists managed to communicate through the fissures among these plates. Using euphemisms, parables and humor, we found ways to zigzag around official control and transmit messages at the least possible risk. The censors, for example, forbid the use of the word «strike.» Franco’s police sequestered the weekly newsmagazine, Cambio 16, for publishing information about a strike, so the next week I wrote a story about the same strike but called it a «technical worker stoppage.» Nothing happened. And just before the death of Franco, one of his ministers, who had been a press censor, solemnly declared: «From now on, we will call a strike a strike.» His statement made headlines. And when democracy came to Spain, the dictionary was restored to journalists.

During Franco’s time, we also learned to print the riskiest information in centerfolds that could be easily removed. That way, if the censor banned the article, we could quickly reprint it with the required changes or replace it with another innocuous feature, thereby avoiding a costly sequestering of the entire publication. Another technique involved substituting objectionable paragraphs with photos.

But the dictatorship also learned to read between the lines. Dozens of times I was indicted for so-called press or opinion «crimes.» With my article about the Civil Guard, in addition to being kidnapped I was indicted by the department of military justice on charges of sedition, despite being a civilian. I did not have a court martial, thanks to an opportune general amnesty for press crimes decreed by King Juan Carlos later that year (1976), just as I accepted my Nieman Fellowship.

These are ways that freedom of expression emerged word by word under the long dictatorship of General Franco. Every banned word and image we managed to defeat was another

A kidnapper was slowly counting; he would shoot me on three if I did not reveal the identity of my sources.

step on our upward climb toward freedom and democracy. For us, there could be no retreat, and our ethical and political convictions gave us strength to resist and keep advancing. In doing this, we were not displaying courage but professional integrity. For this, we would take some risks, but not too many. Actually, we were fairly prudent, and we became artists at simulation and mockery. We were experts at subtly slipping in a word here, another there. We moved about in a dictatorship — and still we move about in our democracy — like a pendulum that looks for equilibrium between passion for the truth and the instinct for survival, between costs and usefulness.

I do not believe that journalists deserve any more merit than doctors, lawyers, teachers, firemen, or engineers who also try to do their job well. The difference is that we work with material that is highly inflammable or explosive — words that give form to ideas and news events. Like others, we only want to do our job well, and we know risks come with the job. But for us, the compensation — when we manage to publish what we intended to publish — is immediate, intense and priceless. I cannot calculate how many times we put ourselves at risk in order to publish a dangerous bit of news. But was it out of personal courage or just for the satisfaction of doing a story well? Or was it for personal vanity?

On February 23, 1981, an attempted military coup suddenly made it painfully apparent that Spain’s young democracy was shockingly fragile. Tanks rolled into Spanish TV and radio stations and all broadcasts, except military marching music, were suspended. The tanks rumbled on toward newspapers. Members of Parliament, and the entire cabinet of ministers, were held hostage for 18 hours by machine-gun toting Civil Guards. When a Spanish TV cameraman managed to leave his camera running, he filmed the coup, and this was later aired throughout the world.

The Parliament members were served sandwiches wrapped in the front page of a special edition of El Pais, the leading paper, with the headline, «El Pais with the Constitution: The coup in the process of failure.» Receiving those words gave hope to the hostages and government ministers who had no news from the outside; they also disconcerted the coup perpetrators. Had the coup triumphed, it is not hard to imagine the fate of those journalists, photographers and cameramen.

Four days after the coup failed, I wrote a story in El Pais that told how the coup attempt was experienced in Brunete, a nearby town outside of Madrid that had been an important battlefront during the civil war. With the coup thwarted, I never considered any special risks involved with doing this story, even though democracy was obviously still fragile under constant military surveillance by the die-hard followers of Franco. Was I daring? Courageous? Irresponsible? What I was doing is only what journalists do in telling an interesting story of tension and inflamed passions in a small town.

That afternoon, the mayor of Brunete visited me and said, «I come unarmed,» which I took to be a threat. The mayor warned me that he could not «contain» some villagers who were planning to burn our house down that night because they were angered by my story titled, «It’s not an argument, woman, it’s another uprising!» After hearing this, we called the national police and my wife, my three-year-old son, and I took refuge that night in the house of Reuters bureau chief, François Raitberger. Nothing happened to our house, and the town’s soccer team won a game against a neighboring town, so the passions dissipated. That, and perhaps a call to order from the national police.

Journalism in a Democracy

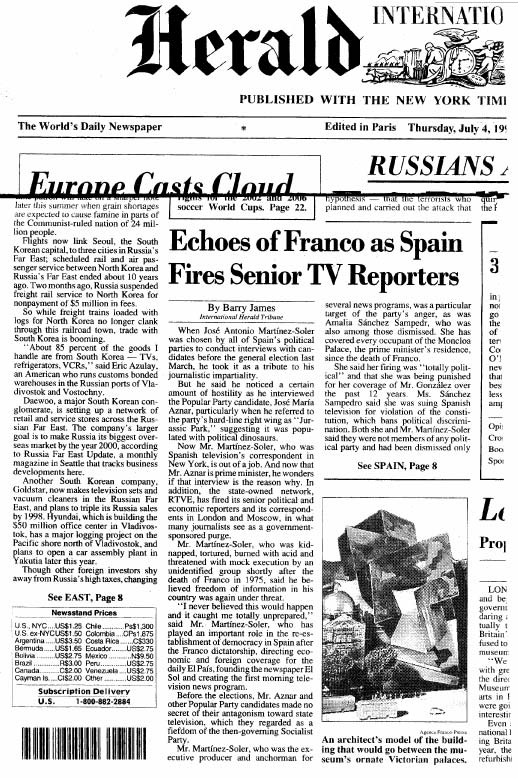

Twenty years after my kidnapping, in fully democratic Spain, I was the television interviewer of candidates for prime minister on state controlled TVE during the electoral campaign of March 1996. I had been called in from New York, where I was bureau chief, to do the interviews. I asked the Popular Party challenger what I thought was an easy, even friendly, question about what he would do with the extreme right wing members of his party, who were popularly termed the «Jurassic Park.» The candidate, Jose Maria Aznar, bristled, fudged a reply, and went on to win the election.

RELATED WEB LINK

Martinez-Soler loses his

job with Spanish Television

(Spanish only)

– 20 minutos)

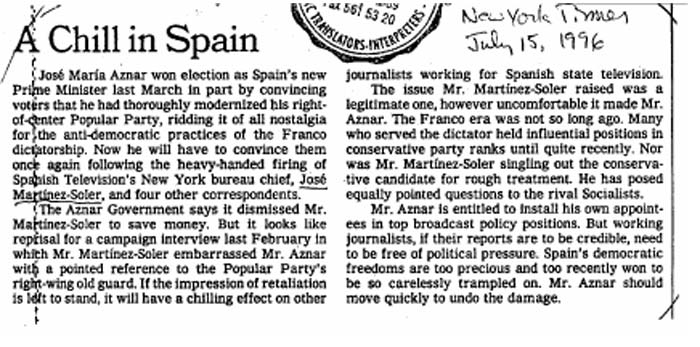

Early in his term as prime minister, Aznar’s government fired me from my jobas the New York bureau chief of Spanish Television. So much for freedom of expression in a new democracy! What journalist would not reconsider his or her questions on the next interview? For me, it became very difficult to find work again in Spain despite support I received worldwide from journalists. The New York Times published an editorial titled, «A Chill in Spain,» and the Financial Times ran an opinion piece titled, «Spanish Practices,» which ended with these words:

«Martinez-Soler, 49, may now well be kicking himself for a lapse in tact during the Aznar interview when he referred to the Popular Party’s old guard as ‘Jurassic Park.’ A former fellow of Harvard University’s prestigious Nieman journalists’ programme, he had also clashed with the previous Socialist administration. Before that, shortly after General Franco’s death, as a young magazine editor, he was kidnapped, tortured and subjected to mock execution, after writing an article about the paramilitary Civil Guard. This time he has merely been sacked from his correspondent’s job. That’s progress for you.»

Jose A. Martinez-Soler, a 1977 Nieman Fellow, is the founder and chief executive officer of «20 Minutos,» Spain’s most widely read daily newspaper based in Madrid with 14 editions in major cities.

Table of contents

Printer-friendly format

(Intentaré traducirlo en fin de semana)